Creating Liminal Spaces of Confession: Johan Deckmann

Copenhagen’s Johan Deckmann's collection of ‘Self-help books’ is deeper than the witty satire on the human condition that they first appear as. This is because of their ability to create an artist out of the viewer.

Many publications have focused on the light-hearted irony of the self-help books that, as a psychotherapist and author, allow Deckmann to “examine the complications of life". I would like to argue that this accidentally, beautifully simple art goes further within than a cleverly witty commentary on society. He uses the depiction of everyday objects to create liminal spaces that are confessional portals entered only by the viewer.

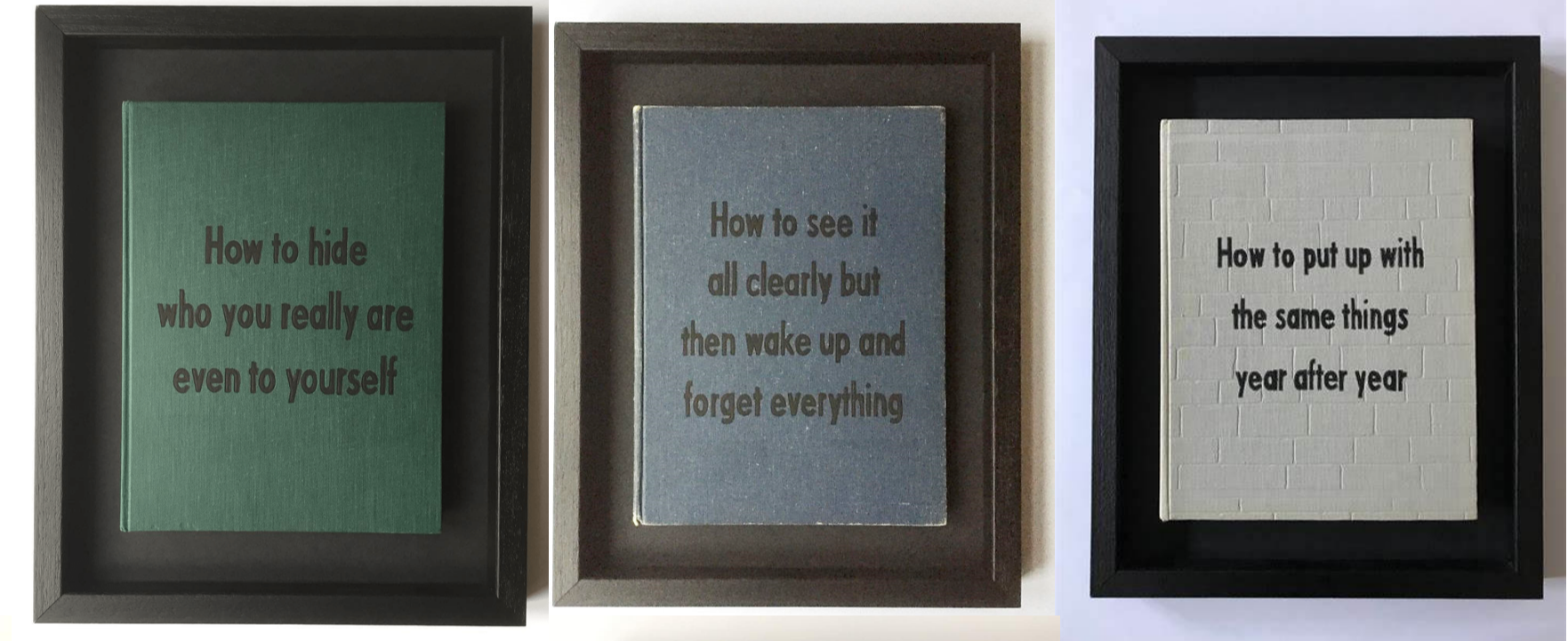

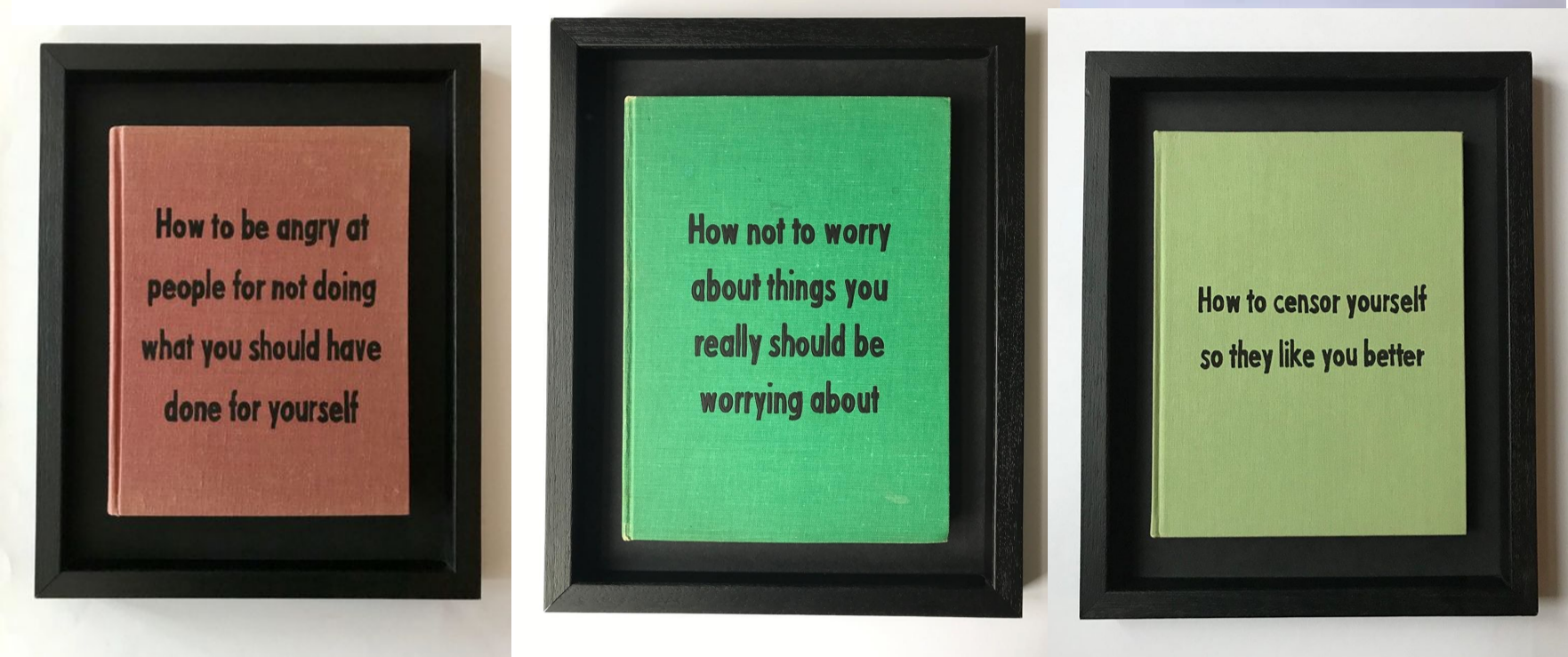

Deckmann becomes the secondary character in the pieces and allows the viewer to take centre stage. By simply framing a book and nothing else, he humbly fades into the background and allows his pieces to be a personal interaction between only the art and the onlooker. Deckmann's pieces create a liminal space that each viewer will fill separately. When we are observing someone viewing these pieces, we are arguably observing them write their journal, curled up on a sofa - this is the intimacy of the collection.

A book is a portal. When viewing someone reading or writing, we are disconnected from them as they fully occupy the space of the text. The only view we have into the portal is the cover, which is simultaneously an invitation and a closed door.

The cover page of a book hints at but ultimately conceals what is only known by the reader. Deckmann uses books and their titles to create spaces for the onlooker to occupy and fill. A space is created within the closed book that the spectator fills with their own confessional art - the unseen pages. He removes himself from the exchange of art with the consumer. By providing the title and nothing else, Deckmann probes the reader to both ask the question and provide the answer themselves. By viewing the art, the reader is coerced into a meditation on themselves and their condition. The books are populated with the secret and silent confessions of the viewer. Whilst there is a secret and intimate element of this work, it also creates a poignant commentary on the universality of the experiences. Each person can populate these books, but their contents exist only in the space of the mind, they cannot be viewed by anyone else – making them the ultimate confessional art.

The collection is also a commentary on what makes a book become itself - is he even depicting books? Or do they remain inanimate sculptures until they are mediated on by the viewer? Is the viewer, therefore, more essential than the artist – the reader more important than the author? Like the viewer takes the place of the artist, they also become the reader and the author. They become the agent of their experience and their perspective.

The ironic but poignant one-liners are weighted with a philosophical and probing attitude towards the human condition. The title ‘How to believe that you only live once but to waste your time like you are going to live forever’ fills the pages of confessional and autobiographical accounts. Records titled ‘The very best of things I should’ve said’/’The very best of things I shouldn’t have said, again, make a space that only the viewer can enter.

Books are associated with the best of the human condition – we make them public, we are esteemed for writing them, and they are often met with praise and appreciation for their art. Deckmann subverts this, by titling and labelling these objects to make them something we would never make into something physical. This is how the collection is so confessional, the liminal space exists only as we are meditating on it. It is not made into something permanent. Through this, we can be completely honest.

Titles such as The Incomplete Truth About Everything are books that we both can and can’t write. Because of their subjective and intimate nature, the collection comments on and examines the nature and reliability of truth and experience – is the incomplete truth all we know, or is all that we know? We both can and can’t fill the pages. In the books that the viewer sees themselves as unable to complete, there is a void, a material manifestation of ignorance. Even though the piece is a two-dimensional depiction, the emptiness and loneliness of the framed book echo in the space between it and the viewer. These are books that will remain empty – subverting the very nature and purpose of their existence. These are questions that we dare not to even ask ourselves, let alone title a book because they both make the idea that we do not know into an object – like an unanswered question hanging in the air.

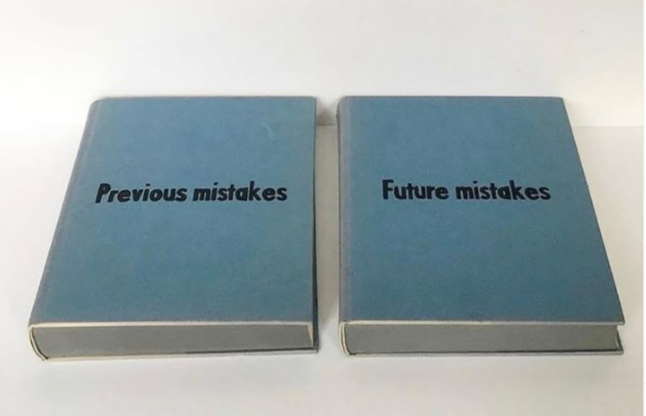

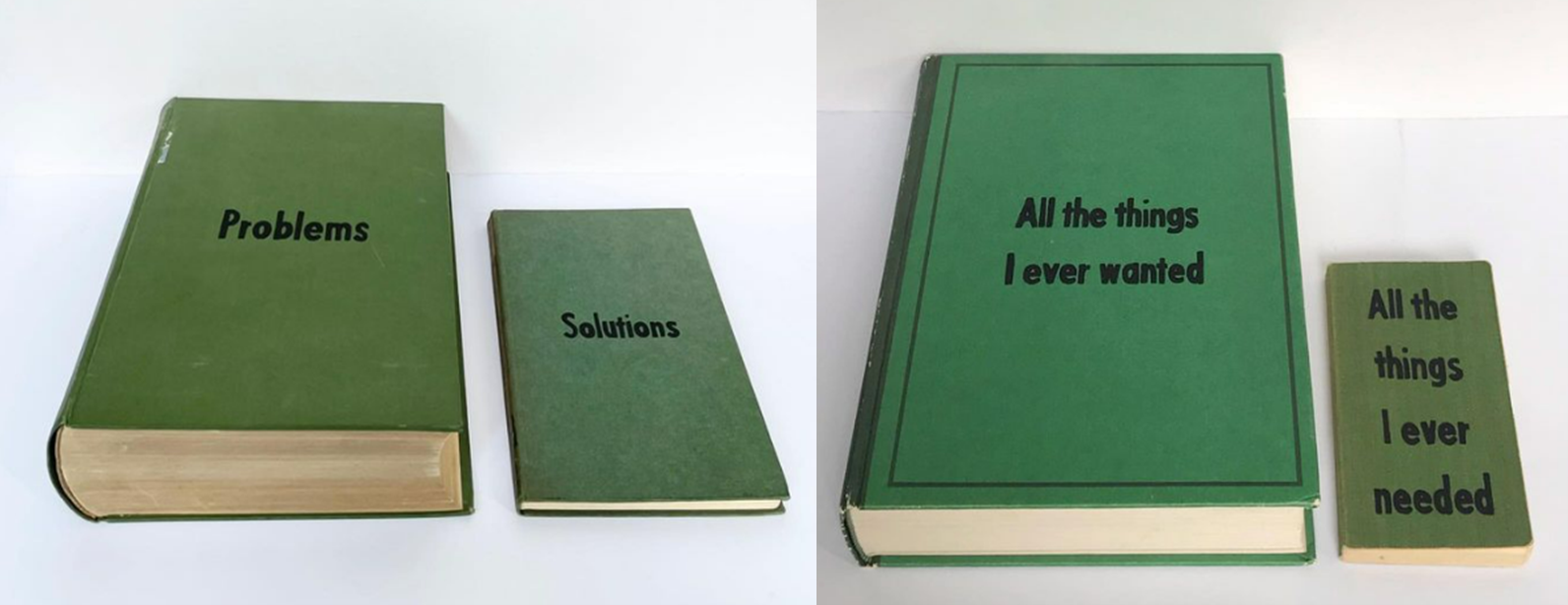

Many of the pieces are titles depicted on their cover page and the depth and size of the books exist only in the imagination of the viewer - beyond the art. For some of his work, however, Deckmann deliberately incorporates the number of pages a book has. By showing two books side by side of different or equal thicknesses, he indicates that the books are already written and are being displayed in their final form. Unlike two-dimensional texts, three-dimensional texts toy with the viewer – there is something in them, but we don’t know what.

Because the texts are completed, a viewer is forced to think of what could be in them, rather than imagine what is in them and then immediately be right. An already-filled book creates a third person in the process of the art, there is the artist, the viewer, and the writer of the book. This mysterious third party is an omniscient and omnipresent being, filling in such books for the viewer that they look upon with something similar to dread but also wonder. In these pairings, there is always a sense of ‘the book of truth’ and ‘the book of what you thought was truth’, again speaking to a commentary on the reliability or unreliability of experience and perception. What is in the other book?

This is summed up perfectly in the ‘previous mistakes’ and ‘future mistakes’ pieces. There is an omniscient author that cannot be the viewer. Rather than being a two-dimensional text, the book taunts a viewer with the fact that it is already written. Its three-dimensionless creates a space we cannot enter with the power of reflection, memory, or imagination: because it is physical, and as fact as it can be.

The thickness of the books is key to their messaging. And the pain or poignancy is in their simplicity. Another piece titled 'Reasons to stay'/'Reasons to leave' is of two books of the same thickness laying next to each other. 'Things I should tell my loved ones before I die'/'Things I tell my loved ones' are of obvious comparative thickness. Their diary-like confessionality makes something internal into a physical object - in turn making it more painful.

Deckmann’s creation of a liminal space through the simplistic and fascinating combination of familiar objects and profound concepts is genius. The art is deeply personal whilst extremely accessible and simplistic.

Post a comment