Siri Hustvedt's essays and collage as an allegory

Collage, when done from other forms of curation such as magazines, newspaper, or art, is the action of dismantling something with an originally intended meaning and making it something completely new.

Feeling uninspired by other mediums I recently decided to try it.

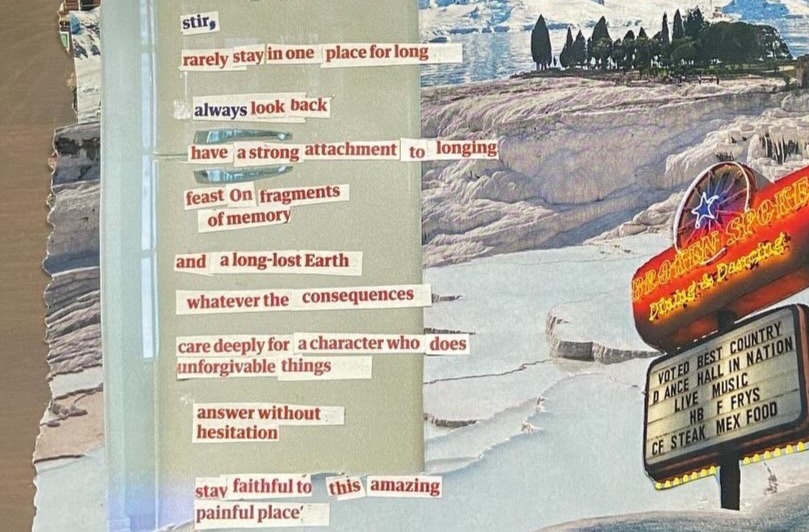

I used the Guardian’s ‘Review’ – a collection of book reviews – and the photos from a national geographic to do this. This was what was in our paper basket; a collection of magazines, flyers, and leaflets in the ‘to read’ pile.

From the book reviews, I found words and phrases jumped out at me, and from these sprang new meanings and new sentences. I was completely enthralled into childishness awe by this process.

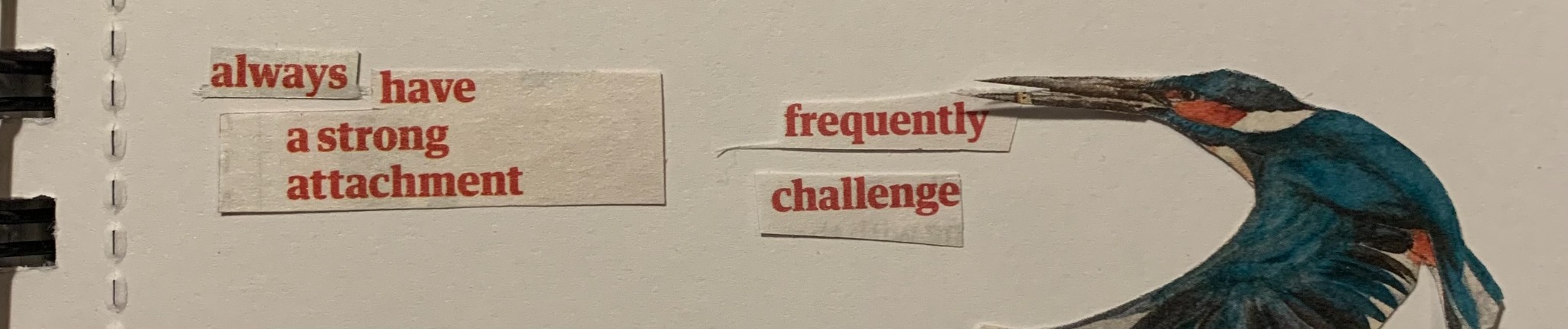

I am a fan of vague but visceral words in art and of phrases that have vivid impact but ambiguous meaning. Neil Farber, Johan Deckman and Michael Dumontier use good examples of this.

A reviewer had written that Pheobe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag makes us care deeply for a character that does unforgivable things. From this came my meaning, by removing makes us, the sentence became an instruction and shed its passiveness. It demanded attention. Care deeply for a character that does unforgivable things. Why should I? Do I already? It suddenly blazes with meaning and confrontation.

By cutting the s off of answers from a different review, again, the sentence became more important, more profound, a warning almost. It made me pay attention and read it. Answer without hesitation, it told me.

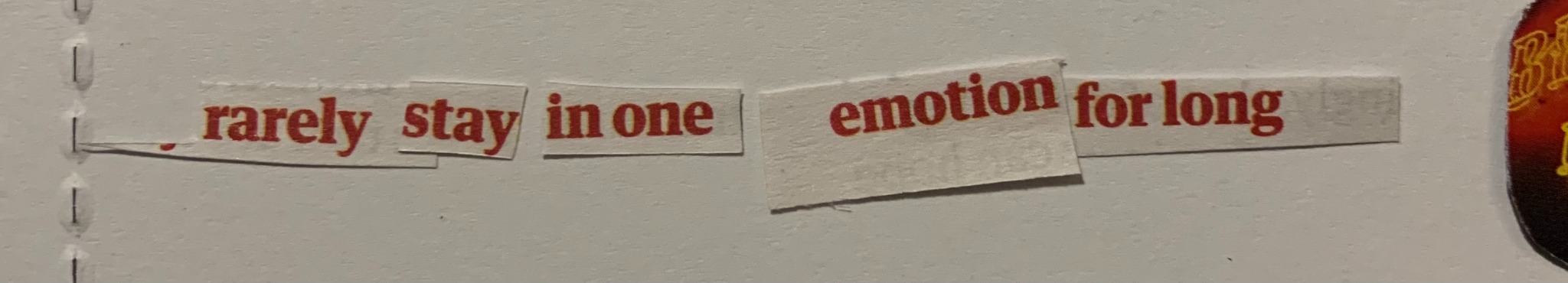

Hockney rarely stays in one place for long, became rarely stay in one place for long. Which almost became rarely stay in one emotion for long as I moved around nouns from other sentences.

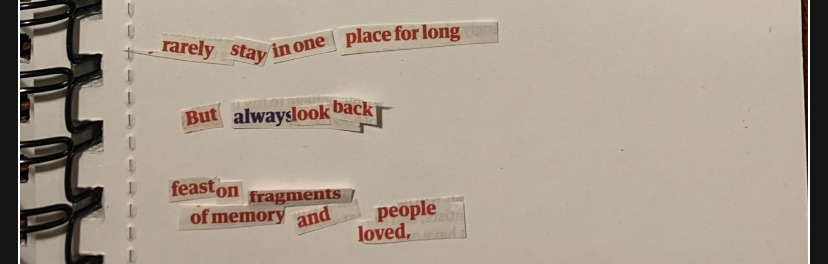

Should we marvel at fragments of memory, feast on, or create them? I could make any one of these with my cutouts of verbs, but, only one.

The limited number of nouns and verbs I had in my clippings made me meticulously experiment with and notice language in a way I never had before and it was fascinating. Chopping up and inverting cliches, marrying nouns and verbs that rarely meet because I had no other option, giving them new meaning and life in the process. A verb which was hardly noticeable in the sentence before has become powerful and I watched it happen.

Should it be rarely stay or stay rarely? Which makes me pay attention to the language more?

The advice the clippings were creating was almost paradoxical, so the grammar ceased to matter. The rhythm of the words became the focus.

But always look back? or the definitive always look back. Which creates a better melody? - Something that Hustvedt references from her writing process: 'I know when a rhythm is right and when it is wrong wrong. Where does this come from?' Where does writing come from?

I felt that this act of collaging words together was a microcosm of writing. Siri Hustvedt, an academic whose writing and experitise spans literature, art, science, and the mind, wrote in The Writing Self and the Psychiatric Patient, an essay from the collection titled A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women, that: ‘I discover what I think because I write. The act of writing is not a translation of thought put into words, but rather a process of discovery.’

Similarly, I discovered what I wanted to mean from the words before me, I was imposing pre-meditated meaning onto them. It was like writing a poem from someone else's mind.

This is like writing. It is not that I know what I mean and then write, it is the inverse. Collage was the physical manifestation of this process. It is fascinating that someone else would have discovered something different in the cut-up words and found a completely separate meaning.

Language surprised me, and phrases that resonated with an aching familiarity created themselves right in front of my eyes, but they weren't from me – would I have put this sentence together if I hadn’t found these disjointed words in this magazine?

I was marvelling at the simultaneous abundance of sentences I could make whilst also struggling with the limits of the phrases I had. Picking from the finite book reviews’ words was allegorical of curating from the limits of our mind, confined by the parameters of language and how we can only express what is within our experience and means to express.

We have limited language. We have limited ways of expression; poets and writers are people who push these limits and boundaries of language.

I wondered also if the writers of the book reviews wondered how their words would be given a completely new significance – do any of us? The minute something is in the world it means a million different things.

When we view art, Hustvedt argues that we are ‘actively creating what we see... we bring ourselves to artworks.’ The perfect allegory for this is me chopping up photographs and paragraphs at my desk to fashion something that meant something to me. The original art was essential, as well as changed and parts disregarded, in my process of finding meaning.

We are always borrowing, using, and repurposing things. We like art because of what we can impose on or find in it. We rarely are moved by art because of the same reason the artist created it. Hustvedt writes in Inside the Room, that ‘Art is always made for someone else. That someone is not a known person. She or he has no face, but art is never made in isolation. When I write, I am always speaking to someone.’

When we read a poem, listen to music, or appreciate art, even if we are not cutting it up and taking it apart, we are imposing new meaning onto it, using other people’s reflections, and repurposing them as something that means something to us.

Hustvedt wrote it best about artist Louise Bourgeois whom she loved: ‘My Louise Bourgeois is not just what I make of her works, not just my own analysis of their sinuous, burgeoning meanings, but rather the Louise Bourgeois who is now part of my bodily self in memory, both conscious and unconscious, who in turn has mutated into the forms of my own work, part of the strange transference that takes place between artists.’

This is what collage became an allegory of.

We all underline different sentences and stanzas in poems, read different books, buy different paintings, and listen to different music. Our lives are, essentially, a collection of others’ art that we have repurposed and mutated and to use in our own work; our life. This is subconscious until we are cutting and sticking it onto blank paper.

Post a comment